In December 2021, Abacus Data conducted a national public opinion survey commissioned by the Rideau Hall Foundation as part of a wider consultation related to strengthening the Forum for Young Canadians program. The survey was conducted with 1,750 young people in Canada, aged 16 to 24, and 700 children (through their parents) aged 12 to 15. The intentions of the survey were to understand civic engagement levels among children and youth in Canada, their perceptions of the space and intentions to engage.

Right now, most young people are interested in civic engagement and eager to know how to become involved.

The majority of youth and children in Canada feel it is important to be active members of their community. 74% of youth and 87% of children feel it is important for them to be active in solving problems in their community.

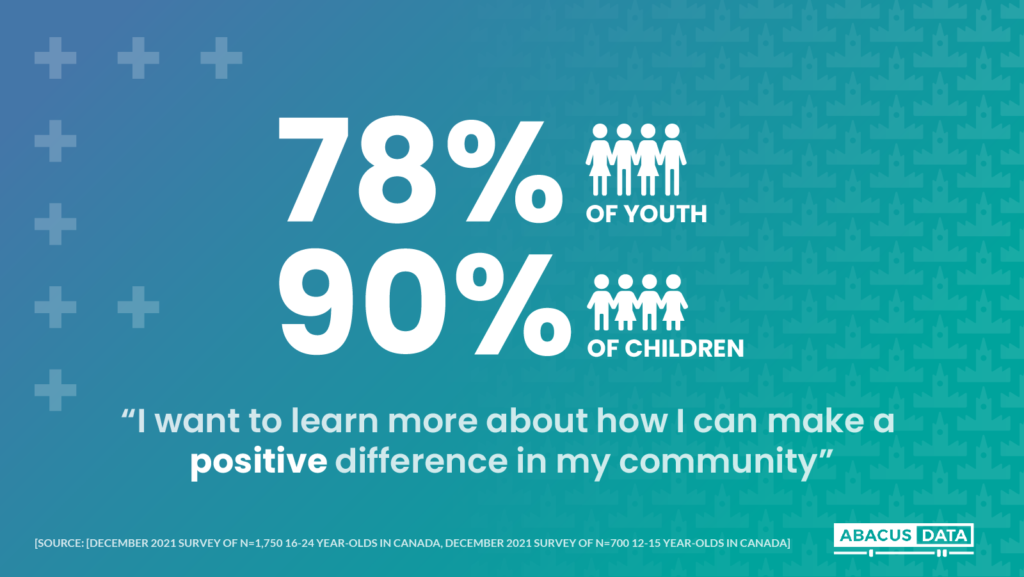

Not only are young Canadians recognizing the importance of taking action, they are ready to put in the work themselves to become more involved. 78% of youth and 90% of children want to learn more about how they can make a positive difference in their community.

When converting their interest to engagement, language is key.

Despite most young people being interested in the ‘concept’ of civic engagement, framing the invitation to participate is critical. They do want to engage but if the invitation seems ingenuine, inaccessible, or unfamiliar they aren’t as interested in participating.

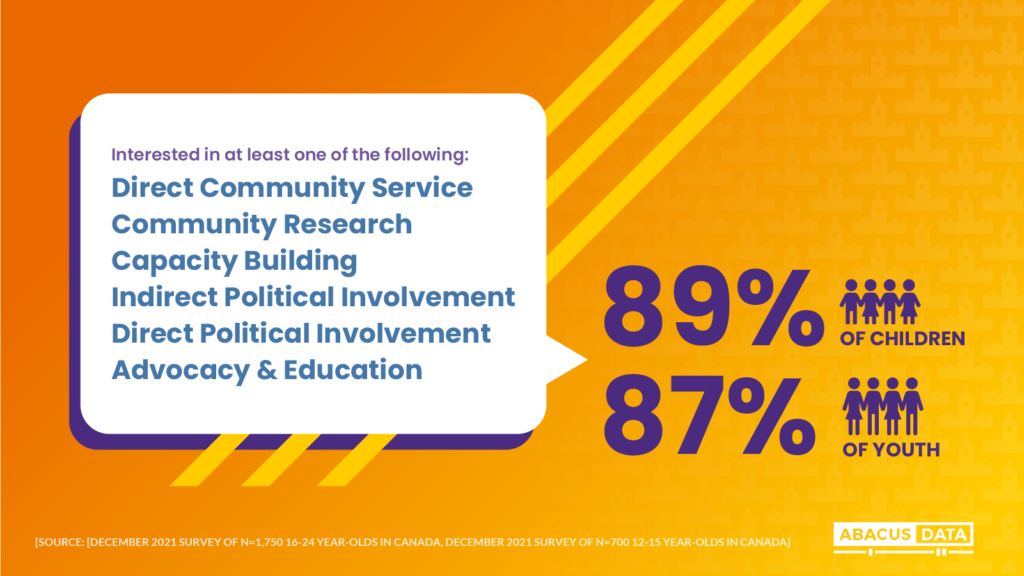

The phrase ‘civic engagement’ itself is a great example of just how much language matters. When given a list of 6 specific types of civic engagement options (community service, indirect and direct political involvement, etc.) 87% of youth and 89% of children are interested in at least one.

However, when we asked if they are interested in ‘civic engagement’ only 69% of youth say ‘yes’ and 42% of children (12- to 15-year-olds) say they do not know what the phrase ‘civic engagement’ means.

Whether the phrase ‘civic engagement’ has less positive connotations, or is just simply not part of their vocabulary, inviting young people to participate works best when they are provided with details about the specific kind of involvement, or the invitation is framed as a way that will lead to solving problems and making a difference in their communities.

Not all young people in Canada have an opportunity to participate in civic engagement, even at a local level and even if they feel it is important.

Interest in civic engagement opportunities is strong, but less than half of youth are currently involved (42%). Interestingly, involvement among children is higher, closer to two-thirds, suggesting that involvement wavers as youth pass through high school.

It’s likely that, as young people grow older, time and cost pressures (the two biggest barriers to involvement) become more of a factor, as youth may need to find a part time job to cover expenses at home, save for post-secondary education, or have other responsibilities that occupy their time.

Another barrier that seems to grow as young people get older is related to confidence. Three quarters of youth (and two thirds of children) say they don’t feel qualified for opportunities they’ve heard of or know about. 63% of youth (and 51% of children) don’t feel welcome to participate in civic engagement activities.

Combatting these perceptions (as well as cost and time barriers) will be important steps to increasing the number of youth who become civically engaged.

Given the gap between the number of young people who are interested vs. those who are currently involved, there is a clear opportunity for growth within the youth civic engagement programming space.

One area with growth potential is showcasing the connection between grassroots organizations and institutions.

Young people tend to gravitate towards grassroots involvement, like volunteering in their community or getting involved with a non-profit, rather than other forms of civic involvement such as pushing for new legislation or changes in government policy. When youth are given the choice between these two types, grassroots involvement wins out two to one.

Young people perceive grassroots involvement as more “accessible”, “flexible” and “less encumbered by rules”, making it easier to see the impact of their service.

As one young person put it, “I think that a big motivating factor of wanting to change the world or impact the world is actually seeing that change or impact take place. Institutionally, even once a person can get to a point where they are able to make a difference or enact change, they may not be able to see the impact firsthand.”

But ask a young person which option is more effective at making change and the options are tied.

In the words of young people themselves, “both categories are important and are co-dependent. Without the grassroots, the institution does not have the advocacy and without the institution, the grassroots does not have the scale or reach”.

Young Canadians are intrigued by making change within institutions and see the value in this participation but are not yet gravitating towards it. Opportunities and programs that increase the accessibility of this type of engagement and expose young people to these avenues for change will be met with a welcome interest. This is a great path to explore when looking for ways to engage more young people in civic engagement.

Finally, to gain experience on the path to becoming civically engaged, young people are seeking an in-person, hands-on experience where they can begin to see the positive consequences of their actions.

68% of youth (55% of children) are interested in a project or initiative that would make a difference in their community. 61% of youth (44% of children) are interested in a multi-day conference or workshop offered once per year56% of youth (48% of children) are interested in a national peer-to-peer network.

Within any of these programs, youth are looking for in-person opportunities that allow them to engage in hands-on and up close and personal opportunities that bring young people together.

As said by a young person with civic engagement experience, “In-person allows for a more immersive and hands-on learning experience. In general, community building is better facilitated when participants are able to meet face-to-face.”

The opportunity to practice skills in a supportive setting and learn from mentors and peers is the most effective approach to drawing young people in and allowing them to see their continued civic engagement impact post-program.

THE UPSHOT

The area of youth and child civic engagement is an ever-growing space, and one with lots of future potential. While youth of today have experienced a number of events in the last few years that have increased the need to experience this potential, also it has also exposed them to the limitations of engagement that exist. And it has changed how one can become involved in their community with the rise of new opportunities and the wind down of others.

Through all of this, young people show great promise for the future. This newer generation’s desire to help their community is clear, and they are ready to do the work to learn and get involved.

We need to take advantage of this motivation by working to eliminate barriers, create a welcoming invitation, facilitate learning in a way that supports young people where they are at, and empower them to make a difference long after the experience is over.

Click here to learn more about this work, and other Forum for Young Canadians research.

METHODOLOGY

The Youth Survey was conducted online, from November 26 to December 21, 2021, fielded to n=1,750 Canadian residents aged 16-24. The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 2.34%, 19 times out of 20.

The Child Survey was conducted online, from November 26 to December 3, 2021, fielded to n=700 Canadian residents aged 12-15 (through their parents). The margin of error for a comparable probability-based random sample of the same size is +/- 3.7%, 19 times out of 20.

The data were weighted according to census data to ensure that the sample matched Canada’s population according to age, gender, educational attainment, and region. Totals may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

This survey was commissioned by the Rideau Hall Foundation.